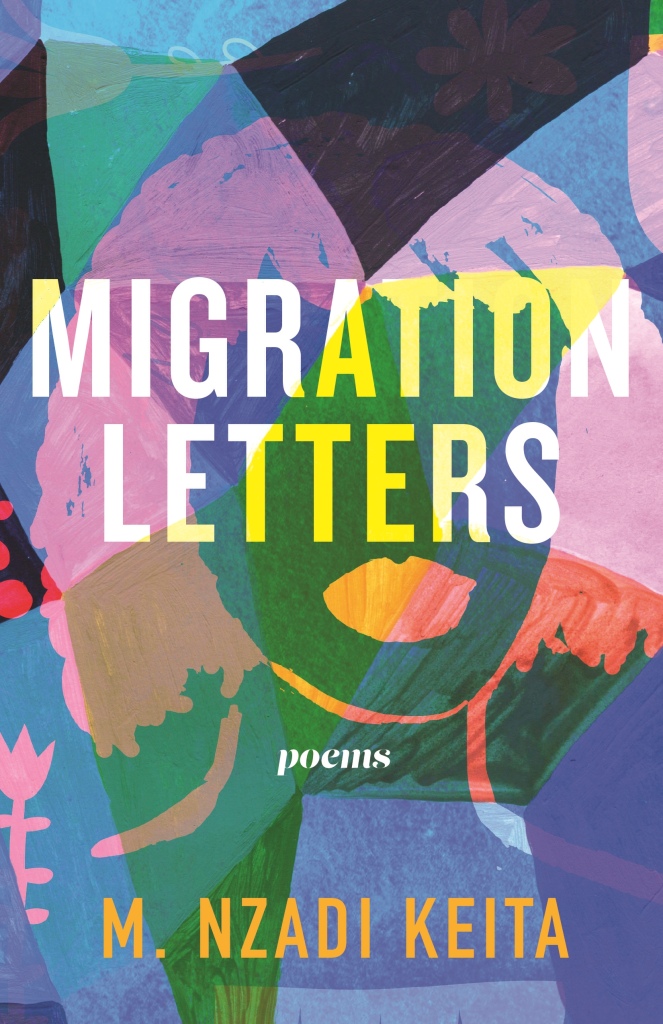

The journey to local poet Nzadi Keita’s latest book, “Migration Letters”, could be said to start all the way down in Georgia. Keita’s grandmother started saving money, cooking for wealthy white families, and selling cow’s milk to her neighbors to buy train tickets to move her family up to Philadelphia.

Or it could start here in Philly, where Keita was born and raised, listening to stories like the ones shared above at her grandmother’s dining room table.

Whatever way it started, Keita, who calls herself a “first generation Northerner,” knew that her personal stories growing up reflected a time in American history that some folks only know from documentaries and history books.

“I was born and raised in the North, I was in Philadelphia, but I was raised by Southern people,” said Keita. She parallels Southern Black folks moving up North with European and other immigrants to the U.S.–their language, customs, and cultural views were different and usually not respected. They worked with little money and tried to work with what Keita’s mother called “motherwit”–a phrase for natural or common sense.

Keita noticed all the differences that she grew up with, being raised by rural Southerners in a northern city. “You’re living a double life. Your old life is still in you and on you, but you’re moving around in the new space, and you have to learn those rules. I grew up with that duality.”

That duality included being raised by parents and grandparents with country roots who knew how to grow food and tend chickens but growing up in a city that didn’t have an abundance of agriculture. “I’m a double-dutch master, but I know nothing about a chicken,” Keita laughs.

From a very young age, Keita loved reading and has always been writing. She graduated from Germantown High School and just retired as an English professor at Ursinus College, where she taught college students for almost thirty years. She and her husband raised two sons here in Germantown at the same time.

She’s published three books, been in multiple anthologies, been awarded numerous writing fellowships, and won the Leeway Transformation Award last year. She’s also taught writing in various settings.

After she published her second book, “Brief Evidence of Heaven: Poems from the Life of Anna Murray Douglass,” she knew she had to continue working on her writing practice. Her lifelong mentor and writing teacher, Sonia Sanchez, ingrained in her the work of a regular writing discipline.

She began a daily practice of writing letters–sometimes to a particular person in her mind and sometimes to people she didn’t know. In the letters, she would write about observations, stories from Philly, and stories of her grandparents’ migration from the South. These letters didn’t necessarily start as poems and didn’t even start with titles. Days were missed, and she continued to work full-time, saving the letters in folders.

Themes started emerging, and once she could go on a writing retreat and gain some space, she could organize and see how the letters evolved into poems and how they fit into at least one book, but probably more. Out of that process came the creation of “Migration Letters.”

“All of these strands are in me, and at some point, I realized there’s too little people know about the Civil Rights movement, the Black Power movement, etc.… but there’s even less that people think about … what happens after that? What happens because of that?”

Poems in the book contain slices of life and historical moments as Keita and her family would watch what was happening on the nightly news. They’re addressed to known and unknown folks ranging from Nina Simone to Mt. Airy and the First Generation North. They talk about the seen and unseen effects of the “secret segregation” of the North–unions that continued to reject Black workers, blocks that Black families knew they were not welcome, and other institutional and cultural rules.

“I remember how Philly was as a child. Nobody was telling me this. I was just looking out of windows and sizing things up. The rules were very unspoken and yet very clear,” said Keita.

Keita said this book took years, and the poems took a lot out of her. But when she could finally hold the book’s physical copy in her hands, she said it “sent her into the sky.”

She talks about the journey, the literal journey of her grandparents and her mother from the South, and her journey of going to college in the five-part poem “Great Migration Pentimento.”

“I thought it was just going to be one poem, but once I wrote it I knew I couldn’t just stop there. It ended up being much more of a faceted journey about me going to college,” says Keita.

She continues: “Because for a first-generation Northerner from a working-class family to go to college, there is nothing matter-of-fact about that. And so I was thinking about my mother and my grandparents and people wringing chicken’s heads off, and I’m going to college.”

She shares one of the five parts entitled “Perry County”:

"When you left for college, you waved back

to grandparents who had raised crops

on land they didn't own. Cooked

food they couldn't buy

from any store. Cut, mopped,

and scoured, brushed, stewed,

and decorated cakes

in kitchens she entered according

to the side door-only rule. Labored

in saw mills, hauling whatever tipped

him closest to risk. Nosefuls of heavy

dangers, iron work. Never designed

to pay enough for savings. For smiling.

For clean favor in the shade."

Nzadi Keita will launch her official book at the Free Library of Philadelphia on Tuesday, April 2, 2024, at 7:30 p.m. at the Parkway Central Branch. She will be in conversation with Herman Beavers. Books will be available to purchase from Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee and Books.