It’s prom season nationwide for high school students of all identities and communities. But, for Black folks, prom may mean a little more. Prom goes far beyond the “school dance” category and serves as a cultural phenomenon in the Black community — in Philly and beyond — and only evolves into something bigger as generations pass.

Historically, prom derives from both patriarchal and racist origins, not making space for anything non-white or non-cisgender and straight. These young social gatherings, originally practiced by college students before being adopted into high school practice, derive from debutante balls, where young women were presented as available for marriage. They were also known as “coming-out” events.

Following debutante balls' footsteps, proms started as exclusively white spaces. Even when schools integrated after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, schools sometimes held two separate proms — one for white folks and one for Black folks. Of course, Black folks have always held their own proms in response. So, at its core, Black Proms are a protest and symbol of resistance.

But also, for many of us, prom is the one night we got/get to transcend our collective adversities, feel celebrated, and create a magical utopia of escapism that reminds us we deserve and are worth more than what we’ve been given historically. It’s an experience that local designer at Gaffney’s Fabrics Valerie Magnum says is “bigger than weddings.”

While I didn’t go to my own prom, I have always found the phenomenon fascinating. Seeing them has always felt like seeing a myth prove itself real. Witnessing someone’s literal material fantasies coming to life in the most creative ways is breathtaking–really.

As an ode to Black Proms, I spoke to locals who either have gone to prom or are doing work close to prom (i.e., giveaways, tailoring, etc.) about their thoughts. Some of the things I was interested in knowing were general observations, how they might compare it to other cultures & customs, how they’ve witnessed its evolution, and what criticisms they’ve heard.

I found three consistent themes from these conversations among the people I spoke to. Those themes are explored below.

It’s both a cultural rite of passage and a celebration of life for Black youth.

As mentioned, the proms have their own rite-of-passage roots, being the event where young folks are essentially introduced to adulthood and to promote social etiquette. While this is still pretty accurate, as mentioned above, some folks might feel that the historical and ongoing adversities of Black Americans make getting to adulthood something to celebrate.

West Philly native Shakira King attended prom in 2009. She points out that prom is still a shared practice across races — not just Black and white. But Black Americans don’t always have other cultural rites of passage like other races and cultures.

King carefully explains: “Black rites of passage are often overlooked because they just look like regular things from childhood. But I don’t think people understand how un-”regular” Black childhood is, especially if you live in a particular kind of city and experiencing a particular kind of poverty or trauma or you're experiencing a certain kind of depression in your city.”

She says that some Black folks need these moments because they’re an “investment in joy,” which she adds is crucial for Black folks.

Crystal Jackson is the founder of the Perfectly Flawless Foundation, which does many things, including providing free prom support services for young ladies. Jackson began this tradition of prom giveaways after hearing about a bad prom experience from a former intern.

“When she left, it broke me in tears,” Jackson recalls. “And I don't cry often, but I couldn't believe I had been spending time with this young lady. Long story short, I said absolutely not. That cannot happen again.”

She plus one’s King’s sentiments about adversity towards the Black community. She says, “I think it's such a huge milestone for any community, right? Any community, but especially us, because we already deal with so much.”

Jackson believes that, as a community, Black folks don’t celebrate or acknowledge their accomplishments enough, saying that alone is a reason to celebrate.

Germantown local Jordan Waynes went on her prom in 2015. She also believes there aren’t many moments to celebrate age transitions and what that means, relating it to other cultures.

“We don't have many events where kids get to celebrate the marking of a period for them,” she says. “Latin culture has quinceaneras and stuff like that.” The others I spoke to echoed these sentiments.

King also talked about the implications of celebrating life more routinely because of upward trends in deaths in younger people, which are primarily caused by suicides, homicides, drug overdoses, and car accidents.

Tarren Hill, who attended her senior prom last year, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of people don’t get to make it to that prom age in Philly like that. I have many friends who didn’t get to go on prom–passed away before prom,” she said.

For King and others, this is more than enough to celebrate these young folks.

“Every opportunity we get to celebrate them, I think we should put them on whatever pedestal we feel is necessary,” said King. “They deserve that level of attention and care. They deserve to be seen in that way. They deserve to have extravagant things.”

She continues: “To have them on this earth still [and] to watch them grow… yes, let's celebrate them. Yes, let's do the most. Like, this is your moment. Be in the spotlight. And I feel like that's what a lot of Black prom culture is.”

It’s a display of both pageantry and community.

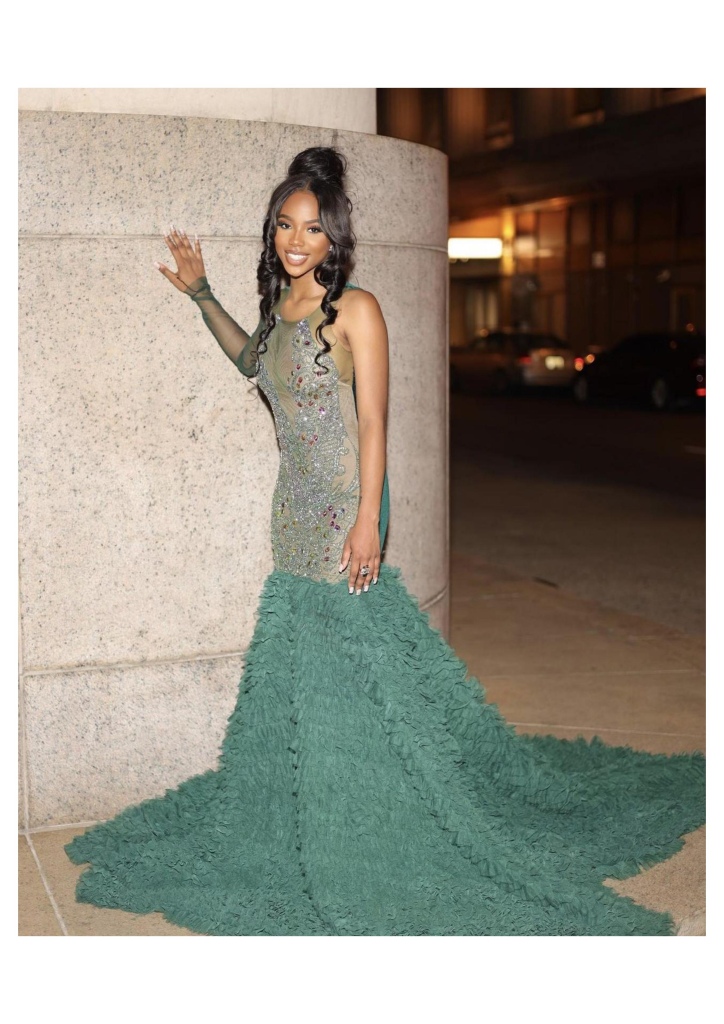

While we have explored the idea of presenting young folks to adulthood via proms, “presentation” has a double meaning when it comes to Black proms. It also, and primarily, means how people look — and how that look is revealed. In this sense, presentation could also be swapped with “pageantry.”

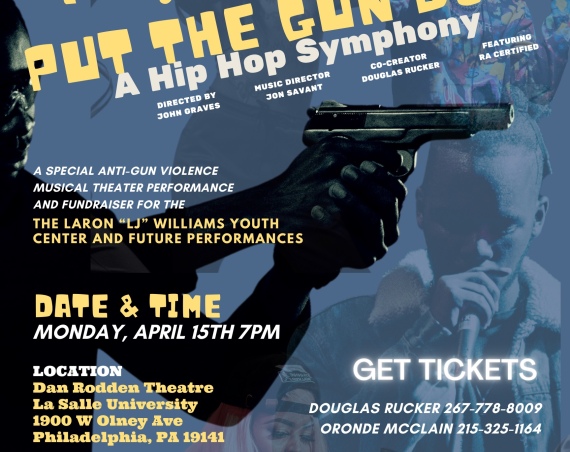

This pageantry is defined by the renowned send-offs, which, in Philly, are bigger than the actual event budding adults attend. These send-offs are where the fantasy comes to life with often custom-made dresses, barbecues, blocked-off streets, rented luxury cars, backdrops & red carpets, recreated moments from pop culture, and even a camel and some rented sand are some things we’ve seen over the years to help make these nights a dream come true.

Hill, the most recent prom attendee, says that she spent more time at the send-off than she did at the prom, which she only recalls being at for an hour.

She remembers her magical night, which she said her family probably spent about $8,000 on. “I had a Barbie box. We had a rental car. We had lots of confetti, lots of balloons, lots of music, and lots of food,” described Hill. She also says that her mother rented an Airbnb just for the send-off.

While King attended high school in North Carolina, she brought the culture with her to prom, which others found exciting. “People were so amazed that I did it big,” she said.

She says that while other Black communities outside of Philly have begun to do bigger prom send-offs, she doesn’t think it became widespread until the 2010s.

She recounted the part of the day to explain her point: "People were so amazed that I was taking my prom seriously because they were preparing to drive their own cars and drive their parents’ car. And my grandmother rented a car for us for the whole weekend, and it was just a whole situation. And I don't think that people down there took it as big.”

She added: “It was a part of Philly that had come to North Carolina. My whole little street was, like, amazed.”

Magnum, who has been at Gaffney Fabrics since 2007, revealed that prom season is her busiest time of year. While she no longer takes over a certain number of orders per season, she once had to complete 30 dresses. And she says that even that number is “minimal” compared to other designers she knows.

“It’s a production,” she said. “That’s been my observation.”

While we do indeed do it big, it should never go unnoticed that these displays of pageantry are also moments that allow the people we know to show us love. It also allows the ones we know to love us a little bit more.

If you scroll Instagram comments during prom season, you may see comments that suggest people do too much for these proms. But, aside from pocket-watching other people, folks could consider who is providing what.

Magnum says that, for her, dress creation, based on what features a person wants the dress to have, can cost anywhere from $900 to $3,000. That’s a lot of money, but consider 2012 prom attendee Sierra Williams, whose late aunt created her dress for her — out of love and free of charge.

Williams said her dress style was popular at the time and described its detailing. “I feel like I might have even seen it pop up on one of them reunion shows or events, maybe an award show. It was silver with sequins and pearls [that] my aunt put on there by hand. And my colors were silver and pink.”

Williams’ aunt passed away four years after her prom and says the dress is now more special than ever. Loved ones covering the costs of things or lending their skills to make the process both memorable and heartwarming is just one of the ways we see community manifest.

The send-offs themselves symbolize traditional Black communal gatherings, almost always including food and, more specifically, cookouts.

“It's almost like a party,” Williams said. “I don't know how to describe it because it's just so ingrained in our culture.”

She compared it to the funerals, which also have their own significance within Black communities. “These are main events and, you know, the events. I took some event planning classes, and they said everything is an event. So it’s just, like, proms are just another event for Black people.”

Waynes has her own thoughts on prom. She, like others you may see, recalls swarms of people coming to hers.

She remembers: “I had a send-off back Germantown, [in] Brickyard, more specifically. I had lived on Clapier Street at the moment. And it was so funny to me because my other cousin (who attended prom the same day) lived on Wister. So you know the distance between Wister and Clapier is literally two blocks over. So, my whole family had to walk from Wister Street [to]two blocks over to see me go off.”

She discusses the significance of these moments, which draw large crowds in the Black community, saying, “Prom really resembles a village.” She says, “You get to see your village that raised this kid [their] whole life. You know, I get to see what I helped create, what I helped raise, go off into the world.”

Hill had similar sentiments, saying that because people don’t see a person on graduation, prom also helps to see that step into a young person’s next stage of life. She said, “You only get a limited amount of tickets. So the prom is, like, the big hoorah where everyone could come [and] everyone could party.”

Waynes also makes an interesting point that reminds us that while prom and graduation can be related, one doesn’t guarantee the other. And so both should be seen as separate but equal moments in a young Black person’s coming-of-age.

She says, “To be honest, I know more people that went to prom than graduated. Just because somebody went to prom doesn't mean they graduated high school. Prom is just a big milestone, especially in the Black community.”

It has evolved since the age of technology, with Philadelphia native Saudia Shuler setting the bar.

While prom has always held some significance for Black people, whether as a protest against segregation or a celebration of life, folks agree that prom has evolved over the years.

Magnum talked more about this, saying she no longer witnessed the usual prom traditions in her work.

“When I first got into [designing], it was just a simple ball gown, sweetheart style. And now it has really evolved,” she said. “Everybody used to just have a little simple prom corsage on the wrist. They don't do that anymore. It's just way, way more than that, you know?”

Magnum says she noticed this shift about ten years ago, which other folks also believe. She attributes this to the age of social media. She explains: “Once we came into technology, everything changed. Yeah. That's when it all got different. Watching Kim Kardashian, watching Beyonce, [and] all the others. Yeah, everything changed.”

Waynes adds her two cents, saying, “You wanna put on your Sunday's best. It's a moment [for parents] to show [their] kid off to the world. For Black people, [prom is] like the BET Awards, [questioning] who’s gonna come out the freshest? This is a competition now.”

Hill says that while “you can see a lot of nice things,” it makes trying to live up to the expectation of prom “a hard thing because it’s so much over the top stuff.”

She adds that the emergence of teen-centered social media accounts like the 5.1 million account followers The Shade Room Teens, which may post different prom send-off videos during the event’s season. Waynes, who is also an educator, says she’s also seen some of her students seek inspiration from and be on the platform.

She believes that the emergence of social media in the last decade has helped make Black proms a cultural phenomenon. She said aside from the “likes and views,” social media has made the exchange of ideas and access to materials and their makers/sellers easier for young folks.

Waynes elaborated: “I think a lot of things wasn't accessible to a lot of little Black kids in the hood, especially these kinds of looks that we going for. But now that I can see the vision, I might know somebody on social media who could tailor a dress. I think it's played a major role in helping, at least, because now I know who got the rental cars. Now I know where you rented your car from. Next year, I'm renting my car from there. I definitely think it's like a gateway to prom.”

While these grand displays serve as a poignant and pivotal moment in the Black community, they are not free from criticism. Waynes gives her thoughts.

“It's pressure. It's a lot of pressure, to be honest. It used to be like this fun thing,” Waynes said. “It still, you know, was the battle who looked the nicest from the early 2000s. But now, you know, everybody wants to be the flyest. But I definitely think it's a lot of pressure now… especially if your folks can't afford [it]. That's my only criticism.”

Ama Jones, founder of Willie Cares, said that while proms are an experience, the competition element can affect the mental health of some young people.

She shares, “I think that Philly makes it more of a comparison. And if you don't have the means or if you don't have the money or you didn't come from a family that can help afford it's, ‘oh, you don't have the money, you're poor. You know, you can't afford this.’ And it becomes an embarrassment. It can cause depression.”

Part of Jones’ mission with Willie Cares is to provide a good prom experience to those who may not have the means to partake in it how they wish. She recently held a prom giveaway event, partnering with rapper JT, half of the Hip-Hop duo City Girls.

Criticisms of Black proms in Philadelphia became much more prominent after one mother, Saudia Shuler of Country Cookin’, sent her son to prom with a “Philly to Dubai” theme. As mentioned before, this prom consisted of shutting the block off, renting a Lamborghini, a camel, some sand, and more, totaling around $25,000.

Williams agrees with this sentiment, saying that Saud “set the bar.” And seven years later, the bar still hasn’t been met.

King remembers the moment in iconic Philadelphia history: "When Saud sent her son off to prom, it was huge. We hadn’t seen [anything like it].” She says that she’s witnessed Shuler's influence, as even one of her own former students made the news for renting a horse and carriage for her prom.

And while the bar has been set, leaving space for folks to criticize, King and others still believe the criticism can be unfair.

“It’s like, why can’t we let these Black children live in a fantasy,” King questioned. “Why can’t we let Black children have these extravagant [wild] things? Why not be a part of the community that gives it to them? Let’s cook these ribs. Let’s have that shrimp. Let’s have all their little friends come over. Let’s have a little dance party. Let’s do all of it.”

Even with her own slight criticism, Waynes believes the oversaturation of opinions is unnecessary. She remembers the big picture–that these events celebrate Black life.

“Mind your business,” she offers, as advice to particularly grown folks who criticize the young people. “Kids aren’t making it to graduation. They aren’t making it to 17-18 without losing themselves to either gun violence… being a victim of drugs [or] being a victim of poverty. So if some want to celebrate their kid making it to this milestone, the end of their academic career, I don't care [they] went out and bought a spaceship. These kids deserve to feel like they on top of the world, but they probably won't have too many more chances to ever feel like that, especially in these kinds of cities.”

Through it all, folks lend sound advice to future prom-goers. Wayne says, “Make memories. The prom night sticks with you for the rest of your life. I could probably remember my whole prom night. Don't get in your head about it… This is for you. This is about you. So have fun.”

King adds: “Y'all, please just live your best life. Dance with your homies. Make the memories. Take every single picture you possibly can. Don't let no teacher ruin your night. And be safe. Go enjoy yourself. Please go be a teenager.”

She ends with a powerful statement: "Black prom deserves to be respected, and it deserves to be held in high regard with all the other cultural celebrations because Black people have culture. And I know that white supremacy makes it seem like we don't, but we do. And we need to claim it and take care of the culture we have because people will come to destroy it. That’s all.”